76 Years Later, A Holocaust Survivor Tells His Story

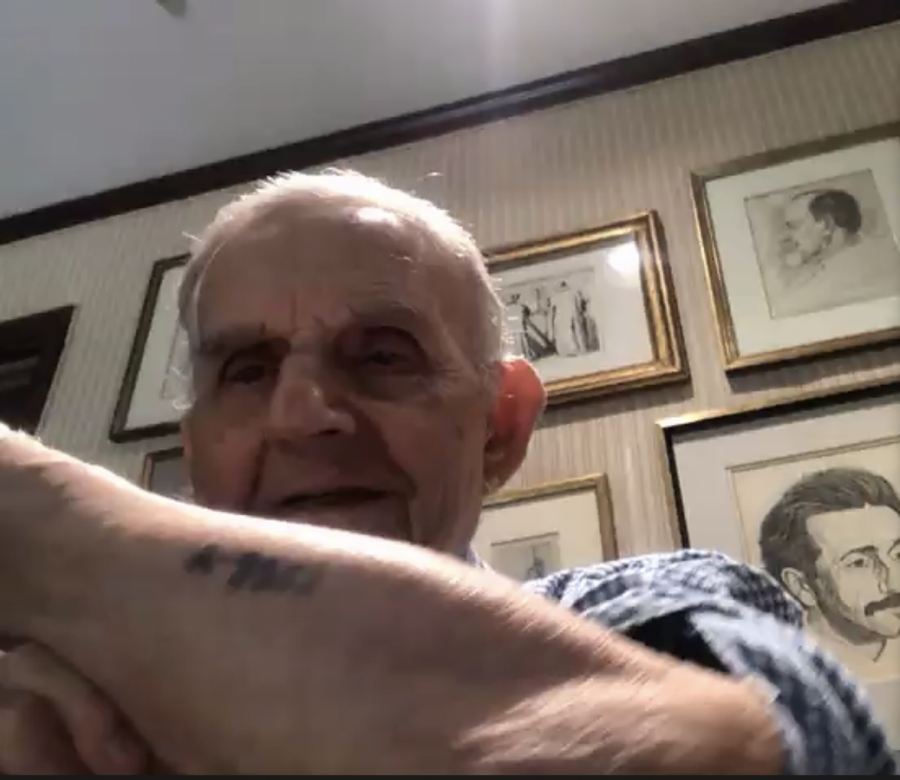

Holocaust survivor Erwin Forley displays his Aushwitz number, A9957, to the School of the New York Times students on June 17 via Zoom.

January 27, 2021

Erwin Forley is getting on board a train bound for Auschwitz. The year is 1944, and Forley is a 16-year-old Jewish teenage boy living in Nazi-occupied-Hungary. The cattle car is cramped and has 100 passengers. Forley smells the rotting flesh of the ghastly prisoners, who have died because of a lack of food and water and the stench from the waste bucket.

The German officer tells the prisoners that the Germans will resettle them in Hungarian Hurtubise (farms). Then he begins burning everyone’s IDs. The train’s wheels start turning, and Forley bleakly looks out through the only window in the dark cattle car. His three-day journey to Auschwitz has begun.

January 27 is International Holocaust Remembrance Day and marks the 76-anniversary of the Holocaust; however, the rise of anti-Semitism around the world threatens the progress made since then. Many survivors, like Forley, are in their 90s, and others have passed away. The danger is that as survivors die, their memories will be lost as well.

“We lived well until the end,” Forley said. “We were happy. We had a happy family. Of course, we heard about what’s happening; most of it we didn’t believe.”

Forley was born on December 6th, 1927, in Košice, Czechoslovakia. His family had a farm and a refinery, and he had a younger brother and an older sister. When he was a child, he went to a Czech elementary and moved to Munkacs, Czechoslovakia. In 1938, Hungary received ¼ of Slovak and Ruthenian territories by the Vienna Award.

“Then the Hungarians came in,” Forley said. “And everything started to go downhill. I went to Hungarian school. Schooling was restricted to 6% of the Jews in the Hungarian schools. Then, I wasn’t able to get in, so I went to Hebrew school.”

Hungarian laws, like the Nuremberg laws, discriminated against Jews. The law restricted the participation of Jews in political and economic life.

“After that, the Germans came in in 1944,” Forley said. “They accumulated us in the ghetto.”

Once he arrived at Auschwitz, Doctor Josef Mengele divided the family. Mengele sent his grandmother and 12-year-old younger brother to the gas chamber. He then separated his sister and mother from him and his father and sent them to work. SS officers tattooed Forley and his father and sent them to work on the farm.

“My father never said that we were father and son,” Forley said. “They were very cruel, and as a punishment, they would hit either the father or the son to make the other suffer.”

SS officers would beat prisoners and unleash German shepherds that tore prisoners apart. When someone died, SS officers would put their bodies in the bathroom.

“You become numb,” Forley said. “I’m a believer, and that’s why I was able to survive. I never left my faith. Jews always hope. In Auschwitz, we also always hoped that we would survive and live.”

Forley may have survived because he did not go on a Death March. He was at the hospital due to a leg injury that happened while he was cutting trees.

“I didn’t see my father after that because he went on a Death March,” Forley said. “In January, they were evacuated, and they went into Germany, and some survived, but he died.”

Soon after, the Russians liberated the camp, and doctors healed Forley’s leg. Forley returned to Munkacs. Out of the 8000 Jews that had lived in Munkacs, only 800 survived. When he returned home, he discovered that a Russian captain had moved into the house.

“I said to the captain, ‘you know I used to live here,’” Forley said. “‘This used to be my house. Can I move this furniture over a little, and he allowed me to move it over, and I reached in, and I took out the pair of earrings that my father had given to my mother.’”

His mother and sister had gone on the Death March, but his mother couldn’t make it. She fell into a ditch, and his sister jumped in after her. The German soldiers left them to die, but German workers rescued them. A few days later, the Russians liberated them, and they returned home.

“One day I come home, I ring the bell, and my mother opened the door,” Forley said. “And that’s how I met my mother; that’s how I knew she was alive.”

Forley then passed through several cities before he reached Prague, where he went to a textile school. He had an uncle, who lived in the United States, and his uncle sent his family immigration documents. Then, Forley took a plane to New York City.

“I found people very nice and friendly,” Forley said. “I took up jewelry designing, and that’s what I did all my life.”

Forley married a Jewish woman named Ruth from Guatemala and raised a family.

“She’s my light,” Forley said. “She is always helping me. [For] the 75th anniversary, I did light a candle at Temple Emanuel. They had six candles for the six million Jews.”

He has shared his story at museums and synagogues to warn the next generation.

“This can happen again in a different form,” Forley said. “Each one of us should do a little bit to fight anti-Semitism and hatred of any race.”